The Architecture of Domination: How Dualistic Categories Enable Oppression and Exploitation

What has dualistic thinking cost our bodies, our relationships, and our planet?

A part of me want to rationalize everything.

To understand, explain, argue.

It’s the part shaped after years in academia, trained to question everything through logic.

While another part listens through the body, surrenders to mystery, remembers that not everything can be named.

This fracture isn’t just mine; it’s a symptom of a historical wound.

An embodied form of a much larger logic: one that builds hierarchies between what is valued and what is not. A logic that considers some subjects, and others objects. That decides which lives deserve care… and which can be discarded.

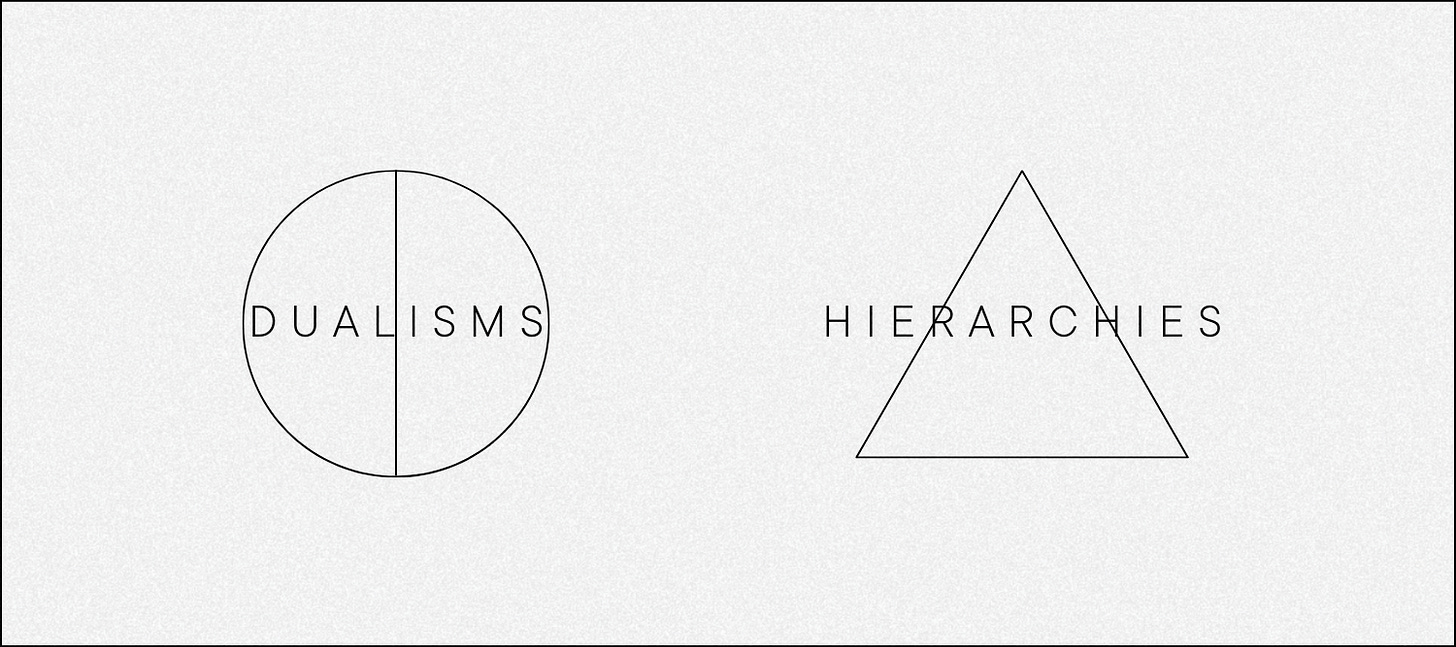

For over two thousand years, the Western worldview has been shaped by dichotomies.

Not just any kind of duality: one where there is no dialogue, only domination.

A logic that splits the world in two, and then determines which half should rule the other.

As Val Plumwood points out, it's a "scaffolding of power": an invisible architecture that shapes not just what we think, but how we feel, what we value, and what we ignore.

This isn't just a way of organizing ideas. It's a structure of power. A system that has legitimized centuries of colonization, epistemic violence, extractive exploitation, and contempt for everything that doesn't fit the mold of the "rational human."

And these dualisms and hierarchies don't stay in the realm of ideas. They become flesh. They become law. They become economies and ways of life.

The roots of the split

Back in Ancient Greece, in Plato's dialogues, the body was already seen as a prison confining the soul—that higher entity destined to contemplate eternal Ideas.

Aristotle, while more engaged with the natural world, upheld this hierarchy by defining the human through its capacity for reason. Physis (nature) was set apart from logos (reason).

This philosophical split mirrored the social structure of the time, where "lower" physical labor was mostly performed by slaves and women, while free male citizens devoted themselves to the “noble” intellectual pursuit and abstract contemplation.

René Descartes took the separation to its extreme in the 17th century. His famous cogito ergo sum (I think, therefore I am) reduced existence to rational consciousness. The non-human world became "mechanical matter" — something to be measured, manipulated, exploited.

Though Descartes didn't directly promote extractivism, his philosophy—this split between res cogitans (thinking substance) and res extensa (extended substance)—was far from abstract.

By stripping nature of agency, it laid the conceptual groundwork for industrial capitalism, the Scientific Revolution, and European colonization.

As Silvia Federici notes in Caliban and the Witch, this new dual ontology (splitting soul from body, production from reproduction, reason from emotion) became incredibly useful to a system that needed to:

Justify the intensive exploitation of nature as mere resource.

Discredit embodied, emotional, and affective knowledge.

Turn human bodies into alienable, measurable labor power.

Subordinate the reproductive (associated with the feminine) to the productive (associated with the masculine).

From Enlightenment to Factory: Instrumental Reason

Instrumental reason didn’t seek to understand the Earth: it sought to conquer it.

The metaphor often linked to Francis Bacon (one of the 'fathers' of the scientific method)—that nature must be tortured to reveal her secrets—is not only brutal, it's revealing.

It reflects the mentality of an era that feminized nature as passive and available for conquest. As Carolyn Merchant explores in The Death of Nature, this metaphor inaugurated a predatory relationship with the Earth.

The Industrial Revolution sealed the deal: bodies regulated by clocks, territories turned into "resources," relationships reduced to transactions. The living became useful. Or disposable.

Forests became "timber." Rivers became "energy sources." Life was commodified; even human time was standardized into factory hours.Coloniality of Being and Knowing

These dualisms didn’t stay in Europe. They were violently exported through centuries of conquest.

The coloniality of power imposed a worldview in which European was rational and civilized, while everything else—Indigenous peoples, relational cosmologies, embodied knowledge—was irrational, savage, backward…

Cultures with non-dual conceptions of existence—where the human and natural, the material and spiritual, formed a continuum—were systematically devalued.

Racial classification itself emerged as a device to determine which beings were "fully rational" and which were closer to "animal nature."

Epistemicide wasn't just a side effect. It was a project.

Objects vs. Subjects

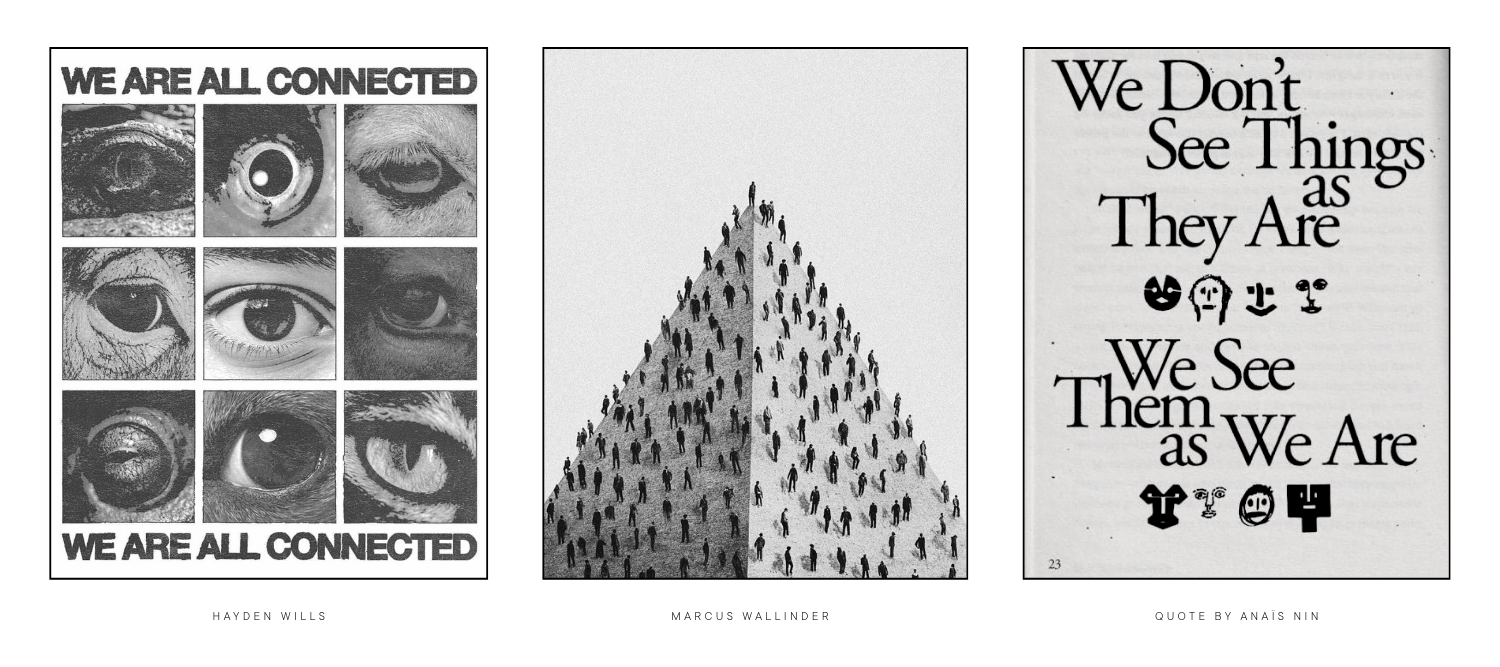

In this logic, it’s not just about separating—it’s about objectifying.

Stripping agency, desire, and voice.

Earth becomes a "resource." Animals become "raw materials." Women become "natural caregivers." Bodies become "labor force."

And all life that doesn’t fit into the mold of productivity or utility becomes disposable.

This mechanism of turning the “Other” into an object—and then ranking it lower—lies at the root of many oppressions: colonialism, patriarchy, capitalism, speciesism, ableism...

And the most insidious part? We often reproduce it unknowingly. Because we’ve internalized it.

The Consequences Are Here

This way of thinking lives on in our structures. And its effects are painfully real:

Ecological collapse: A world that sees nature as a "resource" extracts until there's nothing left.

Alienation: Societies where living in the body, feeling, resting, crying... are seen as a waste of time. The mind-body split has produced cultures where eating disorders, addictions, and the pathology of "not-feeling" run rampant.

Epistemicide: The wisdom of the people, the knowledge of the body, intuition, the art of caring—everything that doesn’t fit into the technocratic mindset—gets sidelined.

Structural inequality: The tasks that sustain life—feeding, healing, raising, caring—are still invisible and undervalued, while capital productivity is glorified.

Sounds familiar?

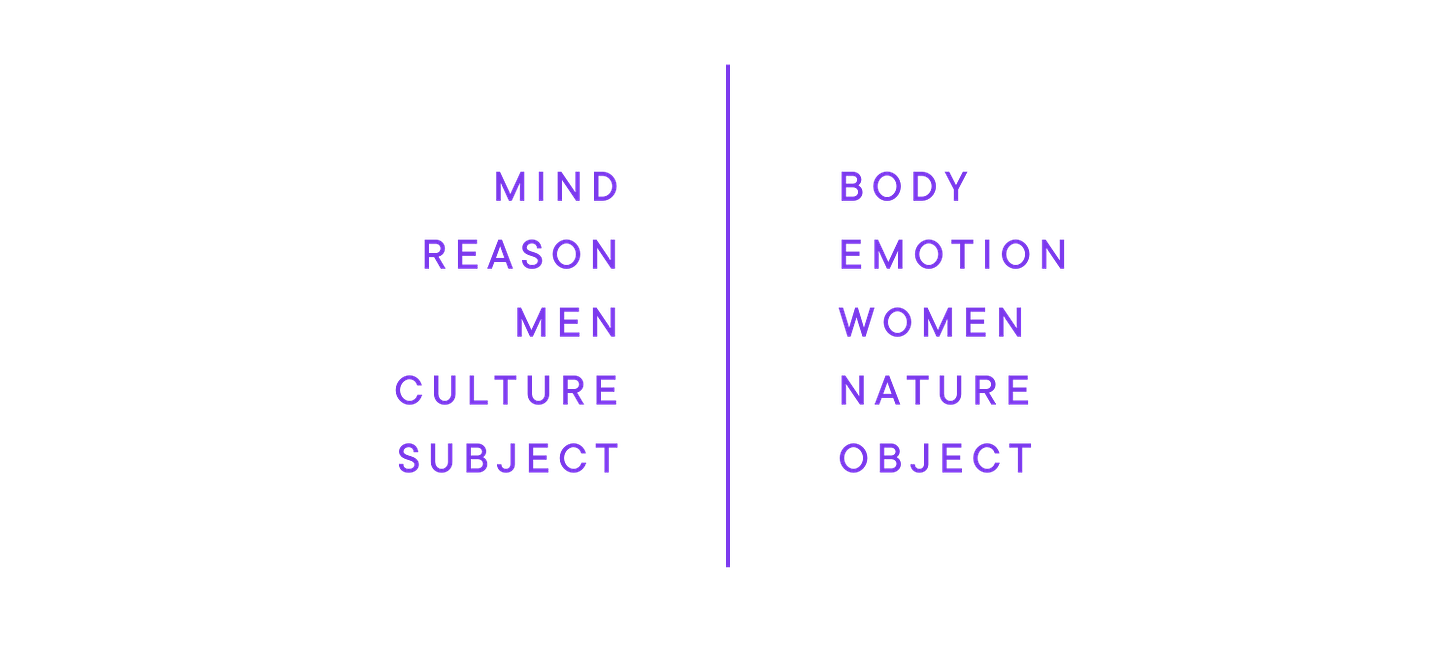

The 'A Side' and the 'Not-A Side'

One of the most illuminating frameworks I've encountered for understanding the dualistic logic that structures thought—and its material consequences—came from reading Carol J. Adams' The Sexual Politics of Meat.

Her analysis, focused on speciesism and patriarchy, reveals how hierarchies are constructed through an invisible table that classifies, separates, and orders everything according to its social and symbolic "value."

Adams proposes what she calls Side A: the masculine, rational, cultural, human, and active versus the other, Side Not-A: the feminine, emotional, natural, animal, and passive.

It’s not about recognizing two aspects of the world that coexist and nourish each other (like the Taoist yin and yang), but rather organizing them hierarchically. It's not about recognizing differences, but about constructing inferiorities.

And once this split is in place, a dynamic of domination begins. The “A” side defines itself in opposition to the “not-A.” It rises by devaluing what it excludes.

What remains on the "other side" becomes a resource: animals become food, women become sexual objects, land becomes raw material —objects versus subjects.

This framework helps us understand, for example, the similarity between language used to describe the "conquest of territories" and "sexual conquest," or the connection between industrial slaughterhouses and other forms of systemic violence against bodies considered "consumable."Objectification is not a metaphor

This logic justifies everything from slavery to climate collapse.

It allows some to be seen as subjects—active, thinking, valuable—and others as objects—passive, inert, usable.

To be treated as an object is to be denied your subjectivity: your ability to feel, to decide, to speak, to matter.

✺ That’s what happens to nature under extractivism.

✺ What happens to racialized and feminized bodies in systems that reduce them to their economic or reproductive utility.

✺ That’s what happens to animals in industrial farms.

✺ And to forest guardians who are murdered for defending land.

This “objectification machine” doesn’t work in isolated parts. It’s a whole system.

Colonial-capitalist-patriarchal modernity depends on this framework: turning life into things, and things into profit.

And it operates not just through violence, but through thought.

Through metaphors.

Through “common sense.”

Through the way we’re taught to divide reality.

It limits our imaginations, breaks our ability to relate, and creates a world that feels increasingly unlivable.Healing the Wounds: Other Ways of Thinking and Living

While facing this hegemonic dichotomies and hierarchical paradigm, other forms of knowledge have indeed resisted.

From non-Western worldviews like allin kawsay (Andean relationality) or the Ubuntu philosophy of southern Africa, life is understood as a network, as connection, as coexistence. Even within Western philosophy, there are cracks in the dominant rationality: Spinoza's monism (♡), which imagines a single infinite substance of which everything is part; or Nietzsche's critique of abstract rationalism.

But if there's one current of thought that has helped me name this wound with clarity—and imagine pathways toward healing—it’s decolonial ecofeminism.

Emerging from the margins, from historically oppressed bodies, decolonial ecofeminism exposes the entanglement between patriarchy, colonialism, and extractivism.

Thinkers and activists like Vandana Shiva, Berta Cáceres, Maria Mies, Yayo Herrero, and Silvia Federici have illuminated how the domination of women, Indigenous peoples, and nature stem from the same colonial logic that separates, hierarchizes, and exploits.

It also recognizes that all oppressions are intertwined: that racism, sexism, speciesism, homophobia, or ecological devastation are not separate phenomena, but different expressions of the same logic.

A logic that fragments and classifies life, that draws lines between what is considered valuable and what can be exploited or discarded.

And it's not just about "adding women" to the environmental narrative, but about dismantling the epistemic structures that have separated us from life.

How many times do we repeat, without realizing it, the gestures of the colonizer toward ourselves, toward others, toward the Earth?Some of the concepts worth exploring through ecofeminism —(I could write loooong pieces for each of them -maybe I will?-)

✶ Intersectionality

✶ Interwoven oppressions

✶ Reintegrating knowledge and body

✶ Ethics of care and the sustainability of life

✶ Environmental justice as social justice

✶ Pluriversal knowledges

✶ Recovering relationality

✶ Putting Life at the center

𖤓 𝚆𝚎 𝚍𝚒𝚐 𝚍𝚎𝚎𝚙𝚎𝚛 𝚘𝚗 𝚝𝚑𝚎𝚜𝚎 𝚒𝚍𝚎𝚊𝚜 𝚊𝚗𝚍 𝚖𝚘𝚛𝚎 𝚒𝚗 𝚖𝚢 𝚢𝚎𝚊𝚛𝚕𝚢 𝚁𝚘𝚘𝚝𝚎𝚍 𝙸𝚖𝚙𝚊𝚌𝚝 𝚌𝚒𝚛𝚌𝚕𝚎. 𝙸𝚏 𝚒𝚝 𝚌𝚊𝚕𝚕𝚜 𝚢𝚘𝚞, 𝚏𝚒𝚗𝚍 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚙𝚘𝚛𝚝𝚊𝚕 𝚊𝚗𝚍 𝚓𝚘𝚒𝚗 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚚𝚞𝚎𝚜𝚝 𝚑𝚎𝚛𝚎:

Towards Complex Thinking

It's not about inverting the hierarchy (now privileging body over mind, emotion over reason), but about dissolving the structure itself.

Adams warns us that it's not enough to reclaim "Side Not-A" without questioning the very structure that produces it as a subordinate category.

True rupture requires dismantling the entire structure.

The "politics of the absent referent"—the mechanism by which beings from "Side Not-A" are erased or fragmented to facilitate their consumption—must be challenged through recognition of the individuality, integrity, and interdependence of all beings, human and non-human.

Putting Life at the Center

The hierarchical dualisms that have structured Western thought are not mere philosophical abstractions: they are power devices with material effects on bodies and territories.

Overcoming them is not an intellectual luxury, but an existential urgency in times of civilizational crisis.

It means practicing ways of knowing and being that do not dominate, that do not reduce, that do not split.

For this, we need new narratives, new practices, new languages. Not to dissolve legitimate differences, but to abandon illegitimate hierarchies.

Because when we stop believing in that separation, we also stop believing in the most dangerous lie of all: that there are disposable lives, existences worth less, bodies born to serve or be consumed.

𖤓

"Nature is an infinite sphere whose center is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere."

Blaise Pascal

𖤓