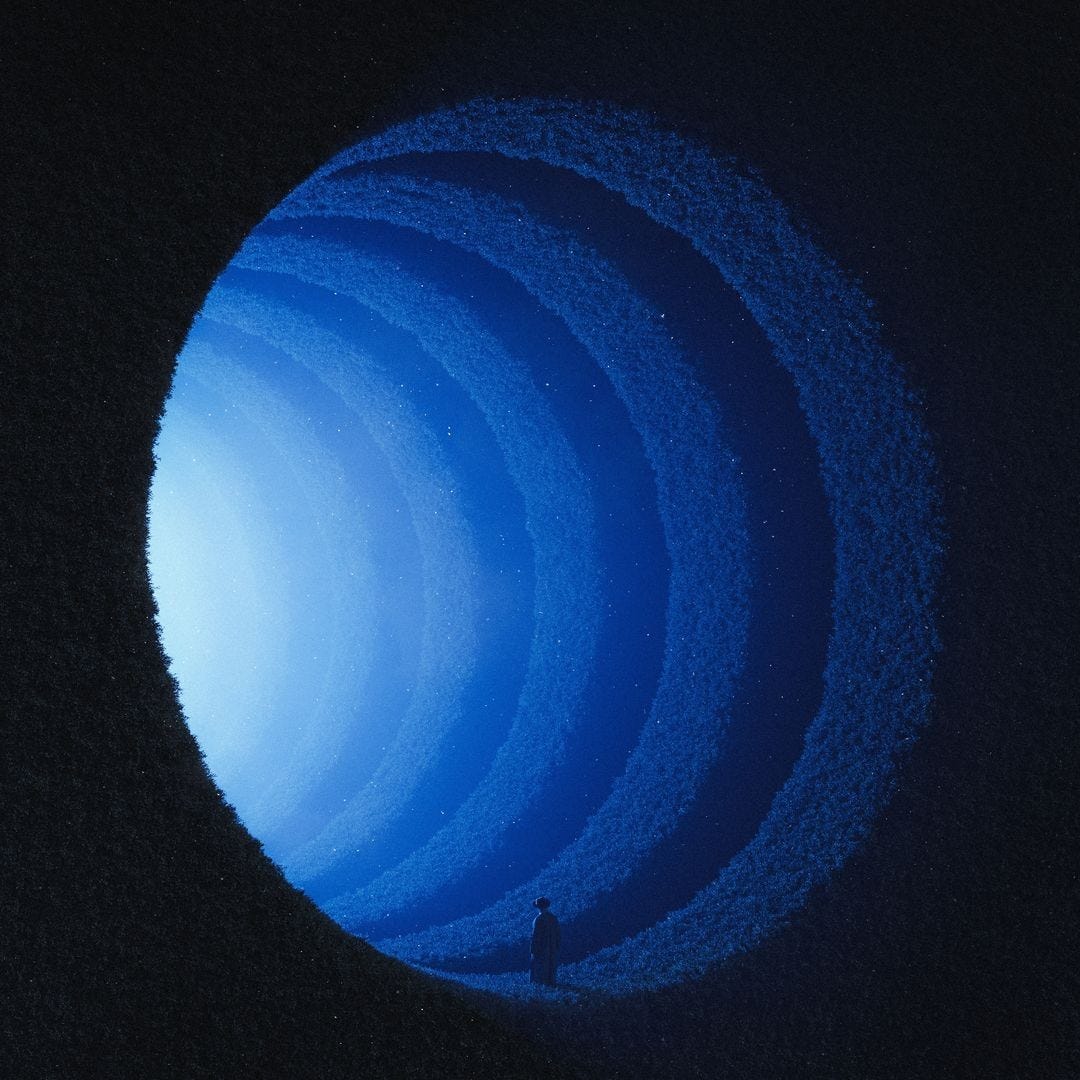

Grief as a Portal to Regeneration

Climate grief, eco-anxiety, and burnout aren’t just personal struggles; they are signals of a world in transition.

Can grief be a door that opens to deeper ways of engaging with the world?

Grief, when it comes, is an unmaking.

It is the collapse of what we thought was stable, the recognition of irreversible loss.

And yet, grief is also fertile.

It is an opening, an invitation into deeper presence, a rupture through which something new might emerge: a sacred threshold between what was and what could be.

In the growing shadow of the climate crisis, our hearts are learning a new language of sorrow. Climate grief, eco-anxiety, burnout—these aren't just buzzwords but lived experiences that many of us carry quietly as we scroll through news of another glacier collapsed, another forest burned, another species silenced forever…

I feel this fully: not as an abstract concern but as a visceral, undeniable truth.

But what if these painful emotions aren't merely burdens to manage or overcome? What if grief itself contains wisdom; a doorway to transformation that our culture has forgotten how to walk through?

Philosophical Pathways Through Grief

Philosophy has long wrestled with grief, not just as an emotional state, but as a fundamental condition of being. This understanding weaves through diverse philosophical traditions, each illuminating different facets of how it can transform us.

Martin Heidegger spoke of Sein-zum-Tode, being-toward-death, as the key to authentic existence. To acknowledge finitude, to sit with it rather than evade it, is to step into a more grounded relationship with life. Similarly, Donna Haraway's concept of staying with the trouble urges us to remain present with grief, to resist the urge to escape into easy solutions or despair.

For Simone Weil explored suffering as a form of attention, suggesting that authentic grief requires a radical receptivity—a willingness to be pierced by reality rather than armoring ourselves against it.

Albert Camus, wrestling with the absurd in human existence, proposed that meaning arises not despite but through our confrontation with mortality and loss. His philosophy suggests that ecological grief might offer its own form of rebellion, a refusal to accept the destruction of our world as inevitable or meaningless, even as we acknowledge its reality.

When we grieve for disappearing ecosystems, we challenge what Judith Butler calls structures of "grievability"—the frameworks that determine which losses deserve public mourning and which remain invisible. When we grieve for ecological loss, we challenge the structures that render non-human life disposable, insisting on their inherent value and our ethical relationship to them.

Indigenous philosopher Kyle Powys Whyte deepens this perspective by situating grief within "collective continuance", where mourning ecological loss becomes inseparable from honoring ancestral relationships and future responsibilities.

These philosophical approaches find their echo in mythology's recurring motif of the underworld descent. Persephone, Orpheus, Inanna… each crosses the threshold into darkness and emerges transformed. These myths reflect something deeply human: the need to ritualize grief, to allow its passage through us so that we, too, might emerge changed.

What if, instead of turning away, we learned to listen to what the darkness has to teach us?

And this is not just an individual process. Throughout history, communities have mourned together, holding loss within shared narratives and rituals. Today, however, grief is often treated as a solitary burden, something to manage privately rather than something that can shape the collective.

Ecological Grief as a Collective Experience

The term ‘ecological grief’ has gained traction in recent years, particularly through the work of researchers like Ashlee Cunsolo and Neville Ellis, who document the mourning experienced by communities witnessing environmental destruction. This grief is not just personal—it is collective, ancestral, planetary. It mirrors the ancient myths of descent, yet in a world that no longer teaches us how to re-emerge.

But here’s the paradox: grief, when fully acknowledged, can be regenerative. It pulls us out of numbness, calls us back into relationship. Grief is not a detour from activism, but a doorway into it.

When we grieve, we declare that we are still connected, still capable of love. And love, as we know, is the root of all regeneration.

Joanna Macy, who pioneered The Work That Reconnects, reminds us that "the pain we feel for the world reveals the depth of our belonging to it." Our grief is not pathology but testimony; evidence of our unbreakable bonds with the living Earth. When we allow ourselves to feel the fullness of this pain without turning away, something remarkable happens: we discover that our capacity to grieve mirrors our capacity to love.

But here lies an even deeper truth—one that turns grief into responsibility: how can we expect anyone to care for what they have not first loved? And how can love take root in a world that has trained us to see nature as background, as resource, as other?

We do not fight for a forest simply because we fear its loss—we fight because, at some unspoken level, we are the forest. The air in our lungs was once exhaled by leaves; the calcium in our bones was carried here by ancient seas. To love the world is to recognize ourselves within it, to dissolve the illusion that our survival is somehow distinct from the survival of rivers, bees, fungi.

This is why grief, when allowed to move through us, is not a weight but a compass. It does not paralyze; it points. It tells us: here is where your love lives. Here is where you must act.

This means refusing to look away from loss: the melting ice, the burning forests, the extinct species. It means acknowledging that what is disappearing will not return, but that our mourning can be a generative act, a way of orienting ourselves toward what still remains and what might yet be restored.

From Collapse to Compost

In nature, nothing is wasted. A fallen tree becomes a nurse log, feeding the next generation of growth. Decay is not an end—it is a beginning. The same can be true for us.

If we allow ourselves to compost our grief, to let it decompose and transform rather than fester, it can nourish something unexpected. It can lead us toward new ways of living, new kinships, new modes of resilience. This is not a passive process but an active alchemy; one that requires our participation, our willingness to sit with grief rather than suppress it.

We see this in Indigenous-led land-back movements, in community-led rewilding projects, in the quiet persistence of those who plant trees whose shade they will never sit under… Grief, metabolized, becomes action.

This is why skipping grief in favor of immediate solutions often leads to burnout.

The urgency to fix things without acknowledging loss can leave us emotionally fragmented, severed from the depth of feeling that sustains long-term commitment. The numbing we so often reach for—whether through distraction, cynicism, or despair—disconnects us from the very aliveness that might guide us forward.

As ecopsychologist Francis Weller writes, "Grief is a threshold element, a profound gesture of belonging that enables us to maintain our connection to that which we love.”

In this way, grief is not a stopping point but a crossroads.

It asks us: will we let this loss harden us into paralysis, or will we allow it to shape us into something more resilient, more attuned to what remains?

Ecopsychologists and somatic therapists consistently observe how unprocessed ecological grief emerges as physical and psychological symptoms—anxiety disorders, immune dysfunction, digestive issues, and a peculiar form of dissociation that psychologist Renee Lertzman calls "environmental melancholia." Indigenous wisdom traditions have long understood what modern medicine is only beginning to recognize: that emotional and physical health are inseparable, that ungrieved losses become embodied as illness. Paraphrasing what Robin Wall Kimmerer writes in Braiding Sweetgrass: grief that is not spoken is a grief that never heals.

When we deny grief its voice, it doesn't disappear but goes underground, emerging in distorted forms—as cynicism, addiction, or the subtle yet pervasive sense that something essential has been lost. We become like trees cut off from their mycorrhizal networks: technically alive but profoundly isolated, unable to access the nourishment that comes from full participation in the web of life.

Beyond the Hero’s Journey

Western culture has taught us to valorize the hero who fights against all odds, who overcomes through individual willpower and determination. But climate work requires a different kind of courage! Not the warrior's push but the midwife's patience, not conquest but accompaniment.

Bearing witness to both suffering and beauty might be our most important practice in these times. This isn't passive observation but active presence, a willingness to stay with difficulty without either turning away or becoming consumed by it.

When we release the need to single-handedly "save" the world and instead learn to move in rhythm with natural cycles of death and rebirth, we discover a different kind of power.

What if the world is not a problem to be solved but a living presence to be engaged?

I've felt this shift in my own body—the subtle but profound difference between acting from frantic urgency versus acting from grounded relationship.

When I slow down enough to listen, to feel my feet on the earth, to acknowledge both the beauty and the brokenness around me, my actions arise not from guilt or fear but from love. And love-rooted action, I've found, is infinitely more sustainable than action born of panic or shame.

In a culture obsessed with productivity and positivity, embracing grief can seem counterintuitive, even reckless.

"Shouldn't we focus on solutions?" the pragmatic voice asks

"Isn't this just dwelling in despair?" the optimist wonders

I've heard these questions; from colleagues, from friends, and most persistently, from that skeptical voice within myself.

This defiance is understandable.

The dominant narrative suggests that to change the world, we must maintain unwavering positivity, that to acknowledge despair is to surrender to it.

When we frame grief as the enemy of action, we miss its power as a catalyst for deeper, more sustainable engagement.

I've witnessed this transformation repeatedly in climate circles. Those who allow themselves to grieve often emerge with clarity and commitment that those perpetually bypassing their emotions never access.

What looks like efficiency—skipping the grief and jumping straight to solutions—often leads to burnout, because we're attempting to heal wounds we haven't fully acknowledged.

Dancing With the Tides: Rhythm and Renewal at the Edge of Worlds

So what do we do with the grief that lingers?

We learn to live with it, not as a burden, but as a pulse… a rhythmic reminder that we are still here, still in relationship with a world that is both unraveling and becoming.

We make space for mourning rituals, for shared lament, for storytelling that honors what has been lost.

And then, we plant. We build. We imagine. We listen for the quiet hum of regeneration beneath the sorrow, knowing that loss is not the end of the story.

Sometimes, in the blue hour between day and night, I sit and simply breathe with the rhythm of the forest.

In those moments, I feel myself as both infinitesimal and integral—a single thread in a vast cosmos of life that stretches back to the first cell and forward to futures I cannot imagine.

This perspective doesn't erase my grief; rather, it holds it in a wider embrace. It reminds me that we are participating in mysteries far greater than our individual lives; that even as systems collapse, new possibilities are being born.

As we stand at this threshold between worlds, may we have the courage to grieve fully, to compost thoroughly, and to remain open to the regeneration that might be struggling to emerge—not despite our grief, but through it.

꩜ What ancient wisdom might we reclaim?

꩜ What new stories might we tell?

꩜ What unexpected alliances might we forge as we learn to navigate a world in transition?

These questions have no easy answers, but in the asking—in the willingness to remain open even in the face of heartbreak—lies our greatest hope for regeneration.

꩜ Because if grief is an unmaking, it is also, always, a portal ꩜

The question is: what will we step into?